#028

Toward a Society for

Aging Peacefully

at Any Place of

Residence

Hiroki Fukahori

Japanese Color: ASAHANADA-iro

#028

Hiroki Fukahori

Japanese Color: ASAHANADA-iro

MOVIE

Professor

Faculty of Nursing and Medical Care

Japan has long been called an aging society, and there is an enormous interest in society in end-of-life medical care, particularly among the growing number of people who want to age gracefully and serenely approach the final hours of their life.

Professor Hiroki Fukahori is intent on ensuring the elderly can age with dignity and individuality regardless of wherever they live, and peacefully progress toward their last hour. He is currently studying ways to raise the quality of end-of-life nursing and medical care at nursing homes and other long-term care facilities for the elderly.

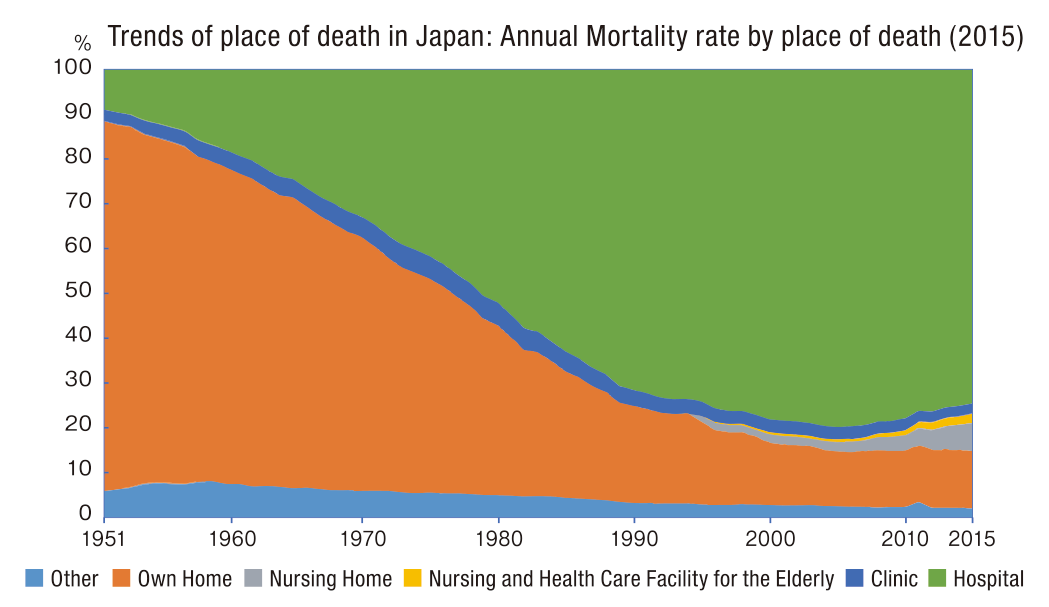

Most Japanese people passed away in their own home up until the 1950s. This gradually shifted to more people taking their last breath at hospitals and clinics, and today around 75% of Japanese meet their final hour at medical institutions. Yet nowadays the number of people passing away at long-term care facilities and their own home is progressively increasing, and this trend is expected to continue from hereon.

Recently, medical institutions are focusing more on end-of-life medical care that respects the patient’s wishes, and the concept of Quality of Death (QOD) to realize a peaceful passing is also slowly spreading in society. There are also various initiatives to ensure people can die with dignity and as they desire; these include Advance Care Planning (ACP), which recognizes that it is difficult for many elderly people to make their own decisions during the end stage of life, and therefore encourages the individual, their family and medical professionals to discuss in advance the treatment and care to be given during his or her final hours.

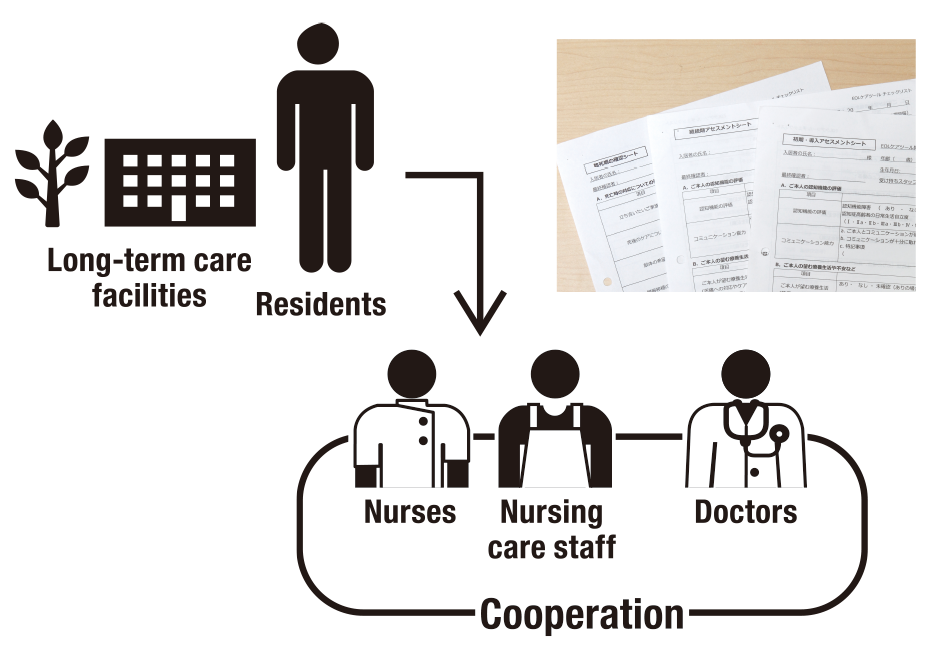

Unlike medical institutions that inherently deal with life and death, long-term care facilities for everyday life offer little support to residents and their families to assist them in determining how to approach an individual’s final hours. So even if the nursing care staff and nurses are aware of the residents’ wishes, in many cases they are not recorded; consequently, sometimes the person receives excessive medical care that they really didn’t want to undergo. I believe enhancing the quality of end-of-life care for residents of geriatric facilities will become a key issue to address in Japan going forward.

So far, end-of-life care has centred around medical practice; yet the tools I’ve created are also being applied and incorporated into educational programs on end-of-life care for nurses, which have been developed in separate studies. However, there are still issues with these tools being difficult to understand for nursing staff, and more than a few of these staff are hesitant to ask patients such sensitive questions about death. We need to improve education on end-of-life care, and develop mechanisms that allow both nurses and nursing care staff to work together to provide quality care.

Currently,over 70% of people in Japan pass away at medical institutions.

According to Cabinet Office Survey (2012) revealed that only 27.7% of people chose medical institution as where they want to spend their final hours. Over 60% of respondents chose their own home, long-term care facilities and other places besides medical institutions. There are currently various initiatives running in the medical care and nursing fields that are aimed at multiple occupations working together to enhance the quality of end-of-life care; the intention is to let elderly people pass away peacefully in the very comfortable and familiar setting of their own home or at a long-term care facility, as much as possible. This is also one of the areas Professor Fukahori is currently studying.

We are currently developing tools to enhance the overall quality of end-of-life care, including finding ways to encourage the residents of geriatric facilities and their families to talk with the nurses and nursing care staff about providing appropriate end-of-life care that will alleviate the pain and symptoms experienced during the final stage of life, while still respecting the individual’s wishes and those of their family.

The tools we are developing in this study are based on tools designed to improve communication among multiple occupations and between medical professionals and patients, and to standardize and improve the Integrated Care Pathway (ICP). Our tools are for use in long-term facilities for the elderly rather than hospitals, and they aim to facilitate regular communication between nursing care staff and residents from when they are still relatively healthy. Depending on the individual’s health and state of their illness, every half-year and 3 months the staff ask the residents about their wishes regarding end-of-life care and check their mental and physical condition by inquiring if they have any concerns or troubles, whether they would like to receive treatment to extend their life, and who they want beside them in their final hour. In many cases, the residents’ wishes remain the same during the period of regularly checking in with them. And although we need to keep in mind the burden on residents by continually asking them these questions, there are also some people who change their mind over a short period due to changes in their health or after experiencing the death of close relatives or friends.

A key feature of these tools is they can be used by nurses and nursing care staff to communicate with residents about their wishes for end-of-life care and other relevant matters. At medical institutions, such questions are asked primarily by doctors; but since there is often no full-time doctor working at long-term care facilities, it becomes the task of the staff there. Also in Japan, when a resident’s current circumstances or illness worsens, he or she is often transferred from the facility to a clinic or hospital for further care. We hope these tools will also be used to share information with and between geriatric facilities and medical institutions about the resident’s wishes for his or her end-of-life care.

The tool used by nurses and nursing care staff is for recording information on the wishes of residents and their families regarding the care provided,as well as information on health areas to test and prescribed medicines,current diet and oral care regime, daily changes in mental and physical conditions, and other data. The staff uses the data collected in the questionnaire sheet to discuss with residents and their families what will be the appropriate end-of-life care to provide when required. The sheet is also a way for nurses to check the latest health information of the residents, so they can know what is the proper care to provide in the residents’final hours.

The tool used by nurses and nursing care staff is for recording information on the wishes of residents and their families regarding the care provided,as well as information on health areas to test and prescribed medicines,current diet and oral care regime, daily changes in mental and physical conditions, and other data. The staff uses the data collected in the questionnaire sheet to discuss with residents and their families what will be the appropriate end-of-life care to provide when required. The sheet is also a way for nurses to check the latest health information of the residents, so they can know what is the proper care to provide in the residents’final hours.

There has long been a problem of a divergence between education and research at universities and the current state of medical practice in nursing. However, students and clinical nurses have been working together to promote evidence-based practice so as to eliminate this gap.

First, the students ask nurses working at medical institutions about what they feel are the current issues in medical practice. Next, the students identify themes from the collected data and research the relevant literature, which they then compile into a review-style paper that is presented to the nurses for discussion. The paper is later reviewed by the nurses to see if it contains any information that may be useful in medical practice.

The students derive immense satisfaction by presenting the paper they have worked so hard on to working nurses, who also benefit by increasing their evidence-based knowledge through the information in the paper. I think this is a really worthwhile endeavour for both sides.

There are currently around 270 universities in Japan offering courses in nursing, and every year many students chose the path of becoming a nurse. I often think the students of today are more brilliant than when I was a university student. Yet, the reality is there are some young nurses who are troubled by what they feel is a gap between what they studied at university and actually working in the field, and subsequently they leave the profession quite early on in their career. I believe it is imperative to develop even stronger links between universities and medical practice to support students in becoming excellent nurses who can apply their acquired skills, and also to facilitate changes in actual medical practice so the skills of young nurses can be utilized.

Nursing is a field in which people provide care for others, and so it is greatly affected by the culture of particular countries and regions. There are countries such as the US and UK that have a logical approach to nursing and a culture of respecting the individual; and then there are nations in East Asia and South-East Asia that place importance on communities and family units. So even in the same field of nursing, I feel the approaches adopted by countries vary due to these differences in basic values.

For instance, Nordic nations such as Sweden and Finland are often regarded as having an advanced model of welfare for the elderly, and the quality of care for older adults is also generally thought to be quite high. Incidentally, I heard from one of my fellow researchers that an expert in geriatric nursing in Japan saw for himself the type of care in Nordic nations that emphasizes an individual’s independence and self-reliance, and he didn’t really feel it was of such a high quality. Conversely, Europeans may find it difficult to comprehend how nurses in Japan can care for patients who don’t communicate their needs or describe their condition.

These differences in approaches motivated me to collaborate with Asian countries that have many shared values with Japan, and we have been conducting joint studies with nursing researchers in East Asia and South-East Asia. Our department is already working with the Hong Kong Polytechnic University and the University of Tokyo on international collaborative research, and we held a joint symposium for Japan, China and Korea at the Japan Academy of Gerontological Nursing general meeting. As for myself, I recognize that I need to work together with and learn from researchers in Asian countries and regions, particularly those from Singapore, Hong Kong and Taiwan where I feel there is an impressive collection of high-quality papers.

Asian nations are also predicted to experience a rapidly aging society from hereon, similar to what’s happening in Japan now. I believe this is another area in which both sides can assist each other, through joint studies and research alliances.

I think there is still so much scope for nurses to apply their medical knowledge and skills and ability to show consideration in everyday life to assist people with illnesses who are living at home or at care facilities. I'd like to work on research to enhance the value of professions that provide care for others such as nursing and nursing care, and that can offer knowledge and develop tools for nurses and nursing care practitioners to use when caring for patients and users of nursing care services.

I like the relaxed atmosphere and challenging spirit of SFC, and I want to make the most of this favourable research environment to deepen ties with clinical practice and in a multitude of professions and fields, including physicians and nursing care. My aim is to make SFC a base for the research, education and practice of geriatric care.

Hiroki Fukahori

Professor, Faculty of Nursing and Medical Care, Keio University. Acquired a Ph.D. in Health Sciences from the Division of Health Sciences and Nursing, Graduate School of Medicine, the University of Tokyo. Completed 2 years of medical practice at Toranomon Hospital, then worked as an assistant professor at the Mie Prefectural College of Nursing, a visiting researcher at the University of Pennsylvania in the United States, and an associate professor at the Tokyo Medical and Dental University, before assuming his current position of professor in 2018. Specializes in health sciences.

2018.Dec ISSUE