#032

Transplantation Medical

Care is Never Ending:

Caring for Pediatric

Recipients is an Issue

Etsuko Soeda

Japanese Color: VIOLET-iro

#032

Etsuko Soeda

Japanese Color: VIOLET-iro

MOVIE

Assistant professor

Faculty of Nursing and Medical Care

The Organ Transplant Law of Japan was enacted in 1997, paving the way for organ donation following brain death. Since then, transplantation medical care has been gradually expanding in Japanese society. As more people’s lives are being saved thanks to transplant surgery, there are calls for creating social structures that understand and support the actual circumstances, feelings and wishes of the transplant recipients. Associate Professor Etsuko Soeda has worked as a recipient transplant coordinator (RTC) at Keio University Hospital, where she provided medical and psychological support to organ transplant recipients. She is currently focusing on researching long-term care for patients who received an organ transplant as a child.

I became a nurse in 1988. Back then I was working at Keio University Hospital’s pediatric surgery department, where many children were battling with biliary atresia – a battle that unfortunately more than a few of those children lost. It was also when I became aware that the situation was different overseas; children with the same disease had recovered, thanks to receiving a liver transplant.

The first time I heard the word “transplantation”, I felt a sense of doubt and discomfort as I wondered, “is such a thing really allowed?” Nevertheless, I strongly felt that if there is a country where lives that would be lost in Japan could be saved, then I want to see for myself what exactly is going on and how transplantation actually happens. So I quit my job and travelled to America in 1992. Incidentally, this was also around the time when the pros and cons of transplantation were just starting to be debated in Japan, following the launch of the Provisional Commission for the Study on Brain Death and Organ Transplantation in 1990.

In America, I was astonished to see organ transplantation being done as a natural and accepted medical treatment; it was as standard as appendectomy. Once I accepted the normality of organ transplantation, my doubt and discomfort toward it vanished and instead I became interested in studying and getting involved in transplantation medical care. My original plan was to return to Japan after six months in America; however, I ended up enrolling in the University of Pittsburgh School of Nursing. After graduating, I stayed on and worked as a nurse, and also studied at the Duquesne University School of Nursing in Pittsburgh. During this time, living-donor liver transplantations had started to be performed at Keio University Hospital in 1995, and in 1997 the Organ Transplant Law came into effect. A system for organ transplantation was also starting to take shape in Japan, and this was one of the factors that prompted me to return there in 1998 and start working as a RTC at Keio University Hospital.

A major difference between transplantation medical care and other types of medical treatment is that the former is never ending. Existing medicine requires transplant recipients to keep taking immunosuppressants for life, yet the medical staff involved in organ transplantations are not necessarily always going to be working in the same unit or out-patient clinic where they can keep monitoring the patients. This is where RTC is needed as someone who can provide continual support to transplant recipients. My role is to respond to any patient who reaches out to me, and I have a notebook filled with information on over 300 liver, kidney, and small intestine recipients that I’ve looked after so far. I’m something of a “lifelong manager” for them.

Organs for transplants can come from deceased persons or living donors. I worked specifically as a coordinator for liver, kidney, and small intestine recipients, and living-donor transplants were overwhelmingly common for the liver and kidney. So I provided support for both the transplant recipient and the organ donor.

Living donors are principally restricted to immediate family members and relatives, and these potential donors need to voluntarily agree to donate their organs. Although family members may also feel pressured and obliged to become a donor if others tell them “you are the only person who is compatible”; and even if they agree to be a donor, it’s not uncommon for them to feel anxious as the surgery approaches. Having a family member who requires an organ transplantation sometimes also brings to the surface issues the family hasn’t been acknowledging. So RTC needs to be sensitive to and aware of the relationships between family members as well.

What if I gave you 10,000 yen? You’d surely be happy to receive it, right? How about if I gave you my organ? Would you be equally as happy to receive such a gift?

The 10-year survival rate of children receiving a liver transplant is currently 80% or higher, while the engraftment rate* for kidney transplants is over 90%. While it is truly wonderful that many lives are being saved thanks to transplantations, the flipside is there will be more children who will live while feeling the weight of having “received an organ.” I’m currently researching long-term support for children who have received a liver transplant, particularly during the “transition period” when the patient moves from receiving medical care as a child to as a teenager and adult.

These children who have received organ transplants face various problems as they continue to grow. They dislike taking certain medication that have adverse effects such as excessive hair growth or hair loss, and once they turn 20, they aren’t sure how much alcohol they can drink. There is also a difference in the warmth of the medical staff in terms of how they interact with the patient in the pediatric department, where the child was treated when they had the transplant the transplant, and as an adult patient in the other hospital departments. The reality is there is insufficient psychological and social care to deal with the growth and changes in children after they’ve received a transplant.

Recently it has become more common to see scenes of organ transplants being performed in television dramas and movies, although they don’t really depict the true feelings and struggles of the donor and recipient. I believe some of the issues we need to address in transplantation medical care are creating more opportunities for transplant recipients to talk about their experiences, and setting up support structures in society for donors and recipients.

※Rate of transplanted organs that are functioning after the surgery.

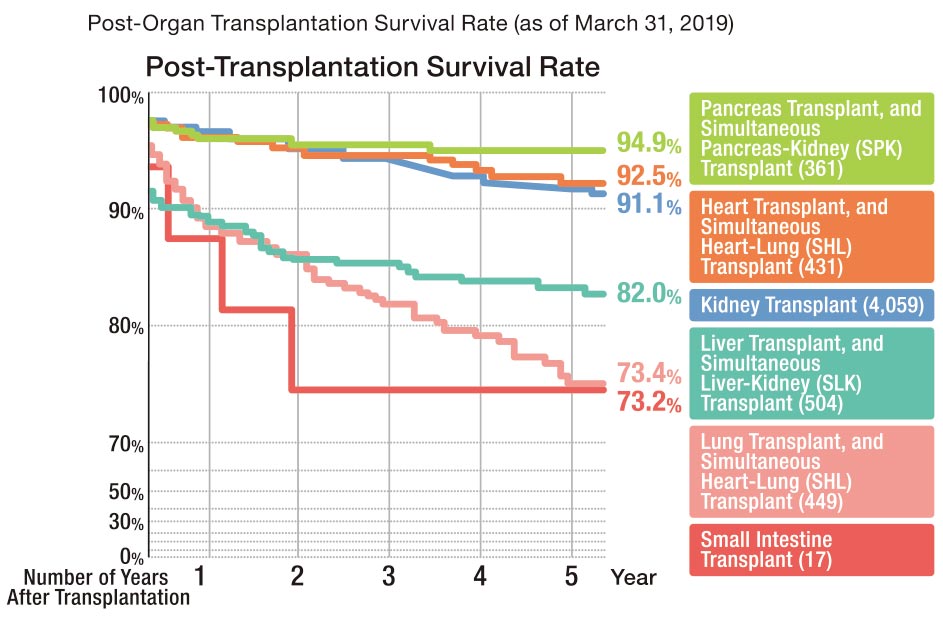

Rising Post-Transplantation Survival Rate

Domestic post-transplantation survival rate from organ donation after death (as of March 31, 2019). Advancements in immunosuppressants have helped to drastically raise the post-transplantation survival rate; however, the number of organ transplants in Japan remains fairly low compared to other countries. This is particularly notable in kidney transplants; although there are about 330,000 artificial dialysis patients, the annual number of kidney transplants is around 1,700. “I’d like more patients to know that transplantation is another treatment option along with blood dialysis and peritoneal dialysis, and to challenge themselves to choose it”, She commented.

Part of my research includes running an annual camp for patients who received an organ transplant at Keio University Hospital as a child. The participants span a wide age group from 4th year elementary school students to people in their 30s, and includes a man who received the first living-donor liver transplant for a child at Keio University Hospital.

At the camp, we survey the participants about things such as their psychosocial skills, moral education and physical abilities, and analyze how the children’s “zest for life” changes through taking part in hands-on activities. For me though, the primary purpose of running these camps is for the children to have some fun.

Every day these children are faced with the same concerns of kids around them such as study, relationships with friends and love-related issues, as well as the stresses associated with being a transplant recipient including hesitation and discomfort about going on a school trip and having their friends see the post-transplant scars on their body. My most earnest wish is for children who have received transplants to be able to get through these tough times by remembering the fun they had at the camp, and recalling the stories of older kids with the same experiences.

I drew inspiration for this camp from the Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh’s summer Camp Chihopi, which I experienced for myself during my time in America. This summer I started the Keio Origami Project to teach origami to children at the summer camp in America, 3 Keio University nursing students and 1 law student volunteered to travel to America with me to assist with the project. Eventually, it would be great if we could make both summer camps a place for interaction and exchanges between Japanese and American children who have received organ transplants.

(Above)

Children who have received an organ transplant are having fun at Soeda’s camp held at the Keio University Akakura Sanso Lodge. It is also an excellent opportunity for medical staff to see the children express emotions they usually don’t while in the hospital, and to check their activities of daily living etc.

(Below)

Young transplant recipients at the Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh’s summer Camp Chihopi are enjoying folding some origami. Soeda and 5 students from Keio University travelled to America to teach the recipients origami as one of the camp activities.

I’m letting our research lab students to attend the organ transplant conferences held every Thursday at Keio University. Because I want them to experience transplantation medical care as it is practiced while they are student. The specialized medical jargon used during the conference is full of abbreviations; unsurprisingly, these are terms that students wouldn’t be able to immediately understand. However, becoming familiar with the names of medicines used and other terminology is one way to lower the hurdle to working in transplantation medical care.

Among the graduates from our research lab is a nurse who helped to arrange a successful lung transplant in America for a high-school student; she took care of everything from coordinating with the hospital where the transplant would take place, to negotiating with the travel agency. Another graduate nurse is now working as a donor coordinator at the (public corporation) Japan Organ Transplant Network (JOTNW). It makes me so happy to see how my students are refining their sensitivities at our lab, and then continuing to grow and develop their skills.

Training, certification and employment are 3 key steps in developing a capable and reliable recipient transplant coordinator. I was involved in setting up the Certified Recipient Transplant Coordinator (RTC) System, which was launched in 2011. I anticipate this system will assist in producing even more knowledgeable and skilled certified RTC throughout Japan. I’m also involved in the Nationwide Donor Survey conducted by the Donor Survey Committee of the Japanese Liver Transplantation Society. The survey aims to ascertain the health status of living-donors for liver transplants. We are currently planning to use this and other information from the survey to develop findings on safety that will also be of benefit to the donors.

Etsuko Soeda

Associate Professor, Faculty of Nursing and Medical Care, Keio University. Certified Recipient Transplant Coordinator (RTC).Completed the Doctoral Course at the Duquesne University School of Nursing in Pittsburgh, the United States. She is a board member of the Japan Academy of Transplantation and Regeneration Nursing, and a trustee of The Japan Society for Transplantation. Specializes in pediatric nursing, transplantation nursing, and transplant coordination.

2019.Oct ISSUE