#036

Learn from the processes of

laws of nature to “generate”

architecture suitable for local

environment

Shohei Matsukawa

Japanese Color:Tobi-iro

#036

Shohei Matsukawa

Japanese Color:Tobi-iro

MOVIE

Associate Professor

Faculty of Environment and Information Studies

All natural phenomena have physical laws behind them, and so do shapes.We identify laws governing shapes, translate them into a computer program, and use them to realize architecture that responds to the local environment. The method is called algorithmic design.Exploring architectural possibilities using a computer system is “like cultivating plants,” says Associate Professor Shohei Matsukawa.Matsukawa hopes to employ algorithmic design to transform standardized and universal modern townscapes into diverse architectural clusters better fitted to the vernacular context.

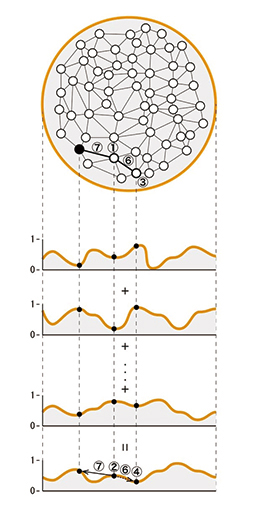

Algorithmic design is a design method based on an algorithm (a process to be followed to solve problems.) Just like all natural phenomena have the laws of nature behind them, specific rules govern the shapes of things. We identify those rules, which are the“pattern”of the shapes, and translate that information into a computerprogram to determine the shapes that have “value.”

The process consists of three phases: the “generation phase,” in which we generate possible shape options using patterns; the “evaluation phase,” in which we quantify the shapes’ fitness for the environment (value) and interpret each shape’s fitness score as an elevation; and the “fitness optimization phase,” in which we aim at finding shapes with higher fitness scores through trial and error, following a hill-climbing algorithm.

For a long time, the capacity to design has been attributed to human senses, experience, and intuition. What we do, however, is use a computer system to “cultivate” architecture and then explore the results suitable for each vernacular context using the algorithmic design method. The process invokes the experience of cultivating living plants. Is it possible to cultivate architecture, like we cultivate plants, by introducing a design process of the insentient laws of nature that results in life and beauty of forms?

The algorithmic design method is constantly evolving as it absorbs AI technology, which has been developing rapidly in recent years. Someday, clients will be able to manipulate parameters and design their homes using a computer system, even if it may take some trial and error. Will architects lose their jobs when AI is more widely used?

Today, AI is regarded as incapable of solving two difficult questions: the “symbol grounding problem” and the“ frame problem.” The symbol grounding problem considers whether AI can connect (ground) a symbol/word to a real-world meaning. In design, this means connecting a shape to a value. For now, it is difficult for computers to recognize or interpret the value of automatically generated shapes, and this responsibility should remain with architects.

The frame problem refers to the situation in which a computer program with a set frame given by a programmer will be confined within that frame. While many people are unaware that they are trapped within a frame of mind called common sense, humans can still solve the frame problem, in my opinion. Identifying the pattern of the shapes, writing a program, and thinking of further possibilities outside that program’s frame are the vital roles of the architect.

When planning my future, I considered three professions: architect, scientist, and teacher. After much thought, I chose architect. Today, I am lucky to teach architecture design on one hand and study buildings using mathematical science on the other.

After running my own architectural office for about 15 years, I took a job at a university to step outside my boundaries. I wanted to work with students to implement the philosophy of algorithmic design in the real world through trial and error without being constricted by my creative limits. Some of my students from the initial study group I organized have started their own businesses and are actively pursuing real-world applications of algorithmic design. The students who have spent time studying the same algorithmic design principles will convey their knowledge to the next generation, instigating changes 50 to 100 years in the future.

Once, architecture was more vernacular, responding to subtle differences in topography and climate to create diverse and unique built landscapes. Commercial housing mass-produced during periods of high economic growth, however, have transformed urban areas into standardized, universal cities. I hope algorithmic design can recreate the original vernacular architecture most suited to each local context. Just as we might spend many years cultivating and tending a garden, I want to dedicate the next hundred years to recreating the scenic vistas of the past.

Shohei Matsukawa

Born in Ishikawa Prefecture in 1974. Graduated from Department of Architecture at Tokyo University of Science Faculty of Engineering in 1998. Established 000studio in 1999. Spent years between 2009 and 2011 as a visiting scholar under the Agency of Cultural Affairs Program of Overseas Study for Upcoming Artists at Harvard Graduate School of Design. Lecturer at Keio University’s Faculty of Environment and Information Studies since 2012. Appointed associate professor in 2014. He co-authored “Designing the Design” (INAX Corporation, 2011) and translated “Algorithmic Architecture” (Shokokusha Publishing, 2010). His work includes AlgorithmicSpace [Hair_salon] (2005) and others.

2023.Nov ISSUE